Indonesia: a podcasting deep-dive

This article is at least a year old

In the latest of our deep-dives into different East and South East Asian podcast markets, we go to the the fourth most populous country in the world - one with their own Joe Rogan, who’s had an outsized effect on podcasting.

What drives podcasting?

Before we can even discuss JKAPAC’s deep-dive, we need to understand what drives the podcasting ecosystem.

Typically podcasts have one of the lowest barriers of entry to creating an “acceptable” audience product. This means that usually it is a creator driven platform - in the sense that you find more willingness for someone to create. But unlike Tiktok or YouTube where it is metric driven (think “Beastification of YouTube”) - most podcasters create because they are inspired.

After listening to the content, is there a reason for the listener to become a podcast creator?

- Does the content have podcast superiority? Or put in another way - does removing, or not having, visuals enhance the value of the production?

- Does the content capture the locality, trends and influences of the time?

- Are there local barriers that prevent one from being a content creator? Is the topic easy to reproduce?

The more often the answer is “Yes!” the more likely content is provided organically into the ecosystem, which eventually creates a category that drives podcast adoption. As one example, Serial is a category driver for podcasting within the US, and has inspired so many true crime creators.

Today in our deep-dive of Indonesia, we’ll explore (1) What stage is Indonesia for podcasting & its history, and (2) What type of content can likely increase the growth of podcasts within Indonesia: ideally creating a Serial-like inflection.

Oh, and one more thing, we’ll share with you all the important metrics that you need - so if you love numbers like me, you’re in for a treat.

Recap

In our last article we explored Indonesia’s Spotify Charts, and realised that the majority of content is about wellness. This reflected a broader trend of Gen-Z interests: topics around loving yourself, being a positive change, and mental health.

Gen-Z topics seem to take the stage because of TikTok, as many of the creators have massive followings that they can migrate over to podcasts.

We also learn that the most popular style is almost ASMR-type, where the form and tone sound comforting, playing well into the emotional aspect of wellness.

Today we’ll learn that Indonesia is going through a period of real and exciting change - some would even argue that it’s reaching an inflection point.

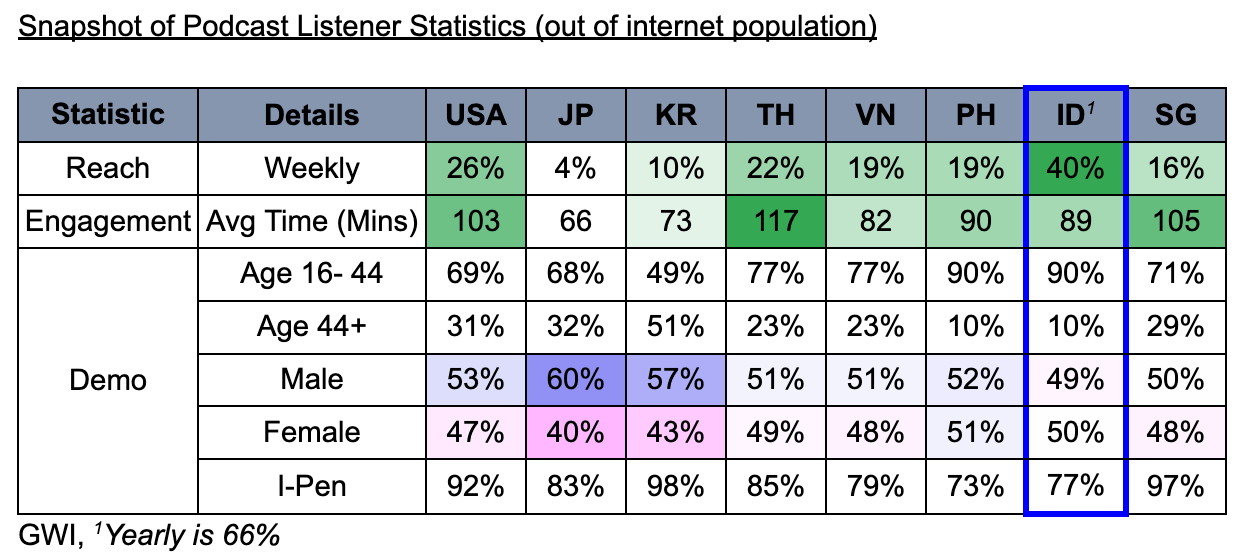

But first - a snapshot of Indonesia’s podcast statistics vs the rest of the region.

- Indonesia has the highest weekly podcast reach (40%), even if you were to adjust to the internet population

- The high reach is not well correlated with duration

- They are almost exclusively younger listeners (<44)

It may seem astounding but the truth is always very nuanced - we believe that a decent number of podcast listeners in Indonesia are misattributing listening to YouTube as listening to podcasts. Bear in mind that GWI actually tries to be specific in telling people that a YouTube video isn’t a podcast, so they’ve tried their best.

The question then is why do we believe that so many people are misattributing YouTube as podcasts? And why despite misattribution do we believe that directionally it’s right - that Indonesia is one of the top nations for podcasting?

The beginning of podcasting in Indonesia (citations at the end)

Indonesia is amongst the 4th largest country in the world by population, which is why there’s a common saying amongst tech companies - that to win in Indonesia would be to win South East Asia.

But as a country it’s fairly different from other well populated nations because the land is split apart by 5 main islands, and over 17,000 other smaller ones. The water divide allows each micro-culture and traditions to develop a lot more on its own vs landlocked countries where it is more diffused.

These waterways are also the very reason why the government has a more uphill task of modernising the country, and to get it connected into the world wide web. With weaker technology infrastructure, especially in the early 2000s, the podcast industry remained non-existent.

Apart for a few pioneers.

Arguably the first is Boy Avianto in 2005 with Apa Apa Podcast. At that time Boy Avianto was studying in Germany, the country which actually triggered Daniel Ek to start investing into podcasting. But it never really picked up because of the poor adoption of technology in Indonesia.

During this period there were others coming in and out of the medium, but it would seem that they would live and die with moderate fanfare.

Then a period of great change started happening within Indonesia - the birth of the unicorns. In 2010, Gojek (the equivalent of Uber in Indonesia) was founded, followed by 2 other startups - Tokopedia (e-commerce), and Traveloka (Indonesia’s version of Trivago). There was buzz all over Indonesia, which was touted as the next “China” in terms of rapid growing startups.

Funds started flowing from all around the world which led to all 3 startups becoming unicorns within the next 6-9 years. These startups then advanced Indonesia’s market rapidly and the country leap-frogged into the smartphone age.

During this period of rapid advancement, interest in the platform was revitalised in the hopes that there would be more audiences. Iqbal Hariadi released Subjective, a podcast in early 2015 where he expresses a millennial opinion on subjective issues. It was relatable, but more importantly a breath of fresh air as most families are very traditional. Filial piety is best displayed with obedience, as such the opinions of neneks (grandmother) and kakeks (grandfathers) often fill the room.

Then like in America, comedy hit the podcasting scene with Adriano Qalby in late 2015, when he released Podcast Awal Minggu, loosely translated to “Early Sunday Podcast”. It’s similar to Subjective but with a good dose of humour. Adriano Qalby’s push on comedy as a tool to make the world a better place led him around all sorts of talks from TED talks, TV, radio that he became known as the “Podcast Father of Indonesia”, a nod to his influence.

During this time another notable early mover is Rane Hafied who founded Paberik Soeara Rakjat with his team, but started with the Suarane Podcast - where he shared personal stories including his time in Bangkok.

All through 2005 to 2015 Indonesia’s GDP per capita tripled, as technology led the charge. Eventually attracting the big boys and Spotify officially launched in March 2016 but it would take another 2 years before podcasts were allowed on the platform in the country.

Rapid growth of podcasting in Indonesia

It’s 2019, and much of Indonesia’s structural barrier to podcasting has been removed. Better yet official podcasts networks were emerging.

Box2Box Indonesia’s first podcast network, then KBR Prime and In-depth Creative

KBR Prime was created by KBR, an independent radio news organisation boasting a network of 500 stations throughout Indonesia. KBR Prime initially existed as an app and later evolved into a Progressive Web Application (PWA) to enable streaming on websites. Leveraging their expertise in the news industry, KBR Prime provided journalism-focused podcast content. Examples include the Disco podcast (Psychological Discussion), Check Facts, and Science Around Us.

Whereas In-depth Creative was founded by Shawn Corrigan, and specialised in both English and Indonesian podcasts. Starting with Indonesia In-depth they move on to produce many hi-fidelity audio dramas, storytelling and documentaries.

Both KBR Prime and In-depth Creative were making the podcast landscape more premium by producing Gimlet and Wondery style content. But it couldn’t catch on as well as the West - not because they aren’t great productions, but it’s likely that podcasts as a medium were so new that the population weren’t ready for the higher mental load.

So, these premium podcasts would remain more niche for now.

Culturally, podcasts weren’t top of mind for the rest of the population even though radio was, and still is popular. To get it into the next stage it had to be creator-led, someone had to make podcasts seem interesting - someone like Joe Rogan.

Deddy Corbuzier or the Joe Rogan of Indonesia, is the most popular Youtube interview style show in Indonesia - who built his audience through controversial interviews. Amongst them were an interview with a rape victim, of which he had asked insensitive questions that prompted her to breakdown on screen.

Regardless of the accusations, it seems that the majority of his audiences love him - his YouTube account has over 20 million followers, and each episode gets well over a million views within a day.

His success story isn’t overnight. Starting off as a magician, he actually won a prestigious Merlin Award given by the International Magician Society. From there he launched his career, and was a talk show host for twelve years before moving into YouTube in 2019.

His popular show titled “Closed the Door” follows a simple interview style format where interviewees sit across a large black table. Like Joe Rogan, Deddy raises subjects randomly but with an overarching theme based on the interviewees expertise.

His open-style interview and of course huge audience base has even attracted the government to release major policy reforms through interviews including the Finance Minister and Defence Minister.

While Deddy is, without a doubt, great at creating clickbait worthy commentary, it’s undeniable that he rode the Covid wave leading to a massive explosion of followers. To keep up he now runs a 40-man team that brings in purportedly US $4.2mn a year.

Now purists would comment that actually Deddy isn’t really a podcaster - he is more a YouTube interviewer. But his contribution to the category is profound because he uses the term “podcast” to describe his high viewership shows.

But this is also why we expect misattribution from Indonesians who confuse a YouTube video interview as a podcast.

Covid had been a terrible year for everyone but incredible for people like Deddy, and of course other notable podcasters like the BKR Brothers, Podcast Malam Kliwon, Do You See What I See by Popo?. The latter two are both horror podcasts, and both Spotify exclusives.

Horror is popular in Indonesia because within Islam the concept of retributive justice (Qisas) is common. Horror themes tend to follow the idea of a vengeful spirit that seeks revenge or retribution, which is why it picks up as a concept.

They are further driven by the TV streaming wars outside of podcasting that is investing in cheap local horror originals.

Another powerful podcast launched at the same time is Spotify’s Podkemas, which follows an “obrolan tongkrongan” style, loosely translated to “hangout chat”, a format that resonates deeply with Indonesian audiences. The podcast was playing to the hierarchical family structure, by bringing in men of different ages and life stages to talk about similar topics in a humorous manner. Podkemas would grow to become a network acquiring other podcasts, and dominate the Spotify podcasts charts for a long time, that is until someone would come and take the form of podcasting to the next level.

A serial-like inflection?

It’s commonly assumed that to gain depth of knowledge, reading is the best way: and to gain breadth quickly, socials or watching a quick video would do the trick.

Podcasts, and content creation seats sort of in the middle - they provide you more depth than a quick read, but an episode is generally less in-depth than if you were to read a book.

In the developed world books are common, but in Indonesia they have been facing a shortage of books over the last decade. For context America’s population is 20% more than Indonesia, but its market value for books as an industry is over 150 times larger.

To make up for the shortfall Indonesia traditionally relied on an oratorical culture - which is why the most senior in the family holds such power.

You can see how this is going to benefit podcasting.

By the end of 2019, earbuds and all the fanciful technology that made podcasting more personal had become cheaper for Indonesians.

Personalisation is a newer concept for Indonesia, as most off city Indonesians stay in a kampung-style home which has less privacy. In these households generalised content is prioritised so everyone can enjoy it.

But with earbuds and smartphones, more people can enjoy their own show, however fringe it might seem.

A new social media platform was also growing in Indonesia. TikTok was allowing the younger generation to amass massive audiences quickly. But most of all it allowed ideas to sweep the nation rapidly, and mental wellness rose as the unifying concept.

Similar to the US, mental health became important for a number of reasons. The first being the generation before them (millennials) often espouse that “it’s not worth the hustle”. After spending years searching for the holy grail called “Ikigai” at the expense of their own health, some millennials feel that it’s a failed promise. To be fair, “Ikigai” has been consumed, repurpose and built into a framework to drive the Western economy - which really isn’t what Ikigai originally is. In Japan only some 31% of respondents in a 2010 survey think Ikigai is work, put in another way if we follow the framework approach, 70% of people would never find their Ikigai.

So if work isn’t the most important thing, then what is? Through social media they would be hit by rhetoric on how your life is more important than your success.

Another important reason is more nuanced because success is increasingly a game of chance with every new generation. The silent generation (Great Depression - WW2) can find success through duty, loyalty and persistence. The baby boomers (Post WW2 - pre 1970s) can find success through out-working their peers. The Gen X (1970s - 1980s) can find success through discovering new opportunities. The Millennials (1980s - mid 1990s) can find success through finding opportunities faster AND outlearning their peers. Come Generation Z - they are inundated with a lot of information on how to build their own business. And most gatekeeper companies are already well established - that can squeeze them out of the market.

As such, to succeed almost feels like a game of chance for Gen Zs - by chance they meet the right people, find the right resource that is better than every other, or by chance they have better genes. Focusing on results is a road to depression, given that it’s less guaranteed than every other generation before them.

So, they focus on the inputs not the outputs - focusing on the small wins, and on taking care of their own well-being.

There are many other contributing reasons but these 2 form a compelling reason why mental wellness is so attractive to them.

Now while global gen Z culture is hitting every nation, back in Indonesia, a term was emerging Galau - used to express an unexpectedly confusing emotion, often heartbreak. Galau’s origins are unclear but it was taking over the country’s social media by storm, and allowing netizens to express depth in their emotions.

The term then weaved its way into the fabric of media - often portraying characters who are struggling with love and relationships. Or in music where the word is explicitly used. To get a good idea, below, a song by Nicole Zefanya (or stage name NIKI) - an Indonesian who was the opening act for Taylor Swift’s The Red Tour.

The empty eyes, happy-sad visuals, lyrics and conflicting vibes is what Galau is.

Effectively all the pieces were set in Indonesia:

- Indonesians are hungry for content - especially since there’s a book shortage

- Technology had allowed personal content to be consumed cheaper

- Distribution channels such as TikTok allowed youths to distribute content rapidly, but also prioritised local relevance

- Concepts such as Mental Health, and Galau were in vogue

All that was missing is the right content that can trigger a wave of inspired content creators and eventually birth a new category of podcasts.

A young girl by the name of Nadhifa Allya Tsana was born in Jakarta, May 4 1998. Not much is known about her family, but growing up it is known that she had a love for writing. Eventually she would submit her written work to the school bulletin boards, but none of them would be displayed.

Young enough to dream, she decided to collect all these stories and write them on a blog. Surprisingly there were actually readers that found it, and one person suggested that she look at Wattpad, a popular platform for budding authors to connect with hungry readers.

It seemed like another distribution channel so she thought why not - the best decision of her life.

Using a pseudonym Rintik Sedu, which loosely translated to “Sobs in Light Rain”, its actual meaning is “Drops of Sadness” in reference to tears. To Tsana she knew her stories would resonate deeply and evoke a strong sense of galau - but she didn’t want the sadness to become lingering. So her name was to express how her works would feel like a light drizzle of sadness that will quickly dry off after reading.

As Rintik Sedu, she wrote many stories. One of her stories, “Geez and Ann”, picked up interest. Geez and Ann starts off following the popular “opposites attract” trope. Geez a singer from a rich family and Ann a studious girl from a poor family find ways to make their relationship work. The tension arises when one has to study overseas. But the book isn’t great because of its rom-com factor, but how well it understands the nuance of family vs relationship in Asia.

No spoilers - but I would say it’s more relatable to eastern viewers.

Gradually bigger publishers heard of “Geez and Ann”, then wooed Tsana to publish the book with them.

Today that book has been adapted into a Netflix series.

Her book sold millions, and she quickly built up a social media following as well ~ 1 million. From there she decided to venture into podcasting - Rintik Sedu.

It was the first time that a podcast sounded so soothing, and patient. She also took full advantage of all her writing experience and filled it with quotes that made every Indonesian listener feel their feelings of confusion were validated and everything would be okay.

It resonated well, then exploded further when Spotify made it an exclusive.

Eventually the podcast overthrew Podkemas for a long time on the Spotify charts.

Given that the format was easy to create - reliant on the podcaster to give a single person narration with minimal SFX & BGM, a whole group of content creators tried their own version of Rintik Sedu. Some even became Spotify exclusives as well - Kita dan Waktu, Gema Membiru, little talks, and Teman Tidur.

These podcasts that are birthing a new category is the reason why Indonesia’s listening time is not well correlated with reach. Because they have very short durations (typically < 30 mins), when averaged against the previous talk show formats with very long durations (> 90 mins) you get a more middle ground average listen duration.

It’s also worth noting, that how some of these podcasts are marketed with names loosely translated as “bedfellow”, which reveals a sad trend of sleep deprivation, According to Sleep Cycle, an app that tracks the sleep across countries - Indonesia ranks surprisingly under 7 hours with fairly low GDP per capita. It means that despite sleeping less - it seems that the hard work or the time spent awake is not translating to higher income or better quality of life. Of course wealth is only an interim measure for happiness.

The birth of mental wellness podcasts and its rapid adoption by independent creators is the most welcome sign for a sustained spike in podcast growth, but that’s not to say that the industry is completely barrierless.

Current day barriers in podcasting

The largest barrier to podcasting is if podcasting is viewed with a purist mindset - only audio without video.

The lines of what a podcast is vs an on-demand video is blurring within Indonesia for a number of reasons. Firstly because of Deddy, and secondly because Indonesians prefer to view content. While we don’t have the hard data to prove this - colloquially through discussions it does seem that Indonesians need visuals more often than Americans in their content. But rest assured you won’t need to create a full blown animation/ movie, something as simple as extreme limited animation - something like what Pocket FM does in India is enough…

The next largest is in the law - particularly law no 11/2018 on electronic information and transaction or locally known as UU ITE. The law is known for putting people in jail for defamation and slander, but isn’t specific on the terminologies. It makes interviewing, and producing content a dangerous game.

According to KBR Prime they are noticing a trend that listeners tend to treat podcasts distributed via music streaming apps as entertainment. This directly contradicts the advantage of podcasts providing knowledge where books are falling short on. Their preferences of what’s an entertaining podcast is also very limited - currently radio style storytelling or chat style is the norm. Anything else, such as long form narrative, audio dramas is actually too complex, and faces lower viewership. We don’t see this as a huge problem, instead it requires more hand holding on creators, because structurally edutainment is an under invested genre.

Another barrier is Indonesia’s reserve nature, which can limit topics. Even someone as controversial as Deddy learns that some lines cannot be crossed. Most notably on LGBTQ+ issues. In May 2022 he posted an interview with a gay couple to share about their homosexual life. Titled vaguely as “Tutorial on being gay” it was quickly taken down when Indonesians accused him of spreading “deviancy”, and giving “deviant’s a space to influence others”. He lost enough followers that prompted him to remove the video, and offer a public apology.

Of course this impacts all forms of communication, not just podcasts - but podcasts tend to have a “real-talk” or more “authentic” equity, which could make it a bigger loser in a reserve country. It’s also worth noting that now laws are in place that made LGBTQ+ conversations even tougher.

The genre of mental wellness also has a risk of content depletion. Unlike true crime in the states where there are hundreds of cases and unfortunately new ones popping up, mental wellness in Indonesia seems to lack a library of source material. Majority of the episodes now are all talking about similar broad concepts, but differentiate by blending it with their personal lives. By nature the average mental wellness creator in Indonesia might have less to go by than a true crime creator in the states - and would likely retire earlier. Would there thus be enough content creators who come in than those leaving to keep the category growing? Possibly, but it does seem wishful to assume this will go on forever.

From the barriers you can tell that podcasts in Indonesia will likely still grow. The question of course is - what?

So what should we launch?

As always, it’s impossible to predict what would be the next category driver in Indonesia, but we can always try.

While interests in topics may fade, structurally it seems that the lack of books has been systemic. In fact it’s been reported for years how Indonesia is struggling with the shortage. Interestingly, audiobooks aren’t necessarily booming in Indonesia… yet, which presents an opportunity for podcasters to make up for the shortfall.

A good edutainment podcast might work real well - and the older podcasts have already shown this to be true. The OGs Iqbal Hariadi’s Subjective, Podkemas, even the controversial Deddy, all have something in common - that they provide new perspectives, often educational perspectives. It could be dressed up with authenticity, humour or just plain controversial fun but a listener can walk off feeling that they’ve learnt something.

Edutainment in Indonesia should serve the long-tail, ideally ever-green pillars of education. A good way is to see what is taken for granted as accessible in Western education - then recreate those topics in Indonesia. Topics such as Politics, Culture & Arts, Global History, General Science, and Finance.

But the format choice in Indonesia is as important as the topic - because an overly premium podcast (think Gimlet/Wondery-style) podcast might have too high a cognitive load. Of course the question then depends if you as a creator/investor/broadcaster want to invest in making the category more premium or capture higher viewership first.

Opportunities to look at more premium shows can be a differentiator, and possibly attract more retentive listeners, but lose general populous appeal. It might be a good option if you embark on a “riches in the niches” strategy.

But for a more broader appeal a hangout chat style (obrolan tongkrongan) format will serve you just fine. And give you consistent viewership of a huge audience base.

While we recommend keeping things simple, it’s important to stay inspired. Geez & Ann has shown us - that style can come from anywhere, especially in the Netflix production which looks nothing like an Indonesian lifetime drama. Instead it has soft pastel colours that permeate the show - almost like an international indie film.

Hence our suggestions will be a mix, drawing inspirations from the west, Indonesia, and within Singapore (where I’m from):

- Premium Edutainment Wondery shows - Business Wars, Business Movers, American Scandal.

- Premium Edutainment Indonesian shows - most shows in KBR Prime and In-depth Creative, but you can check out Nyaris Tamat.

- Finance Edutainment, in a chat show format - The Financial Coconut which introduces Singaporeans to all the best financial strategies that fit the unique Singaporean life / The Woke Salaryman that provide entertaining perspectives on personal finance, investment & career.

- History Edutainment single host chat show format - Half-Arsed History which introduces listeners to general history with a good dose of humour.

Podcasting in Indonesia will likely still grow, not to mention now that NOICE, an Indonesian audio platform, is ramping up against Spotify. NOICE is founded by Rado Ardian, an ex-Accenture/ Googler, and investors include Raffi Ahmad - one of the most popular media personalities in Indonesia. The platform is a publisher like Spotify, but they are also fast becoming an audio super-app.

Integrating western app designs and eastern super-app style structures, the app has all sorts of audio formats on their platform, including live chats, video and creator monetisation mechanics built in (Premium, Micro-transactions). They also disproportionately invest in both originals and exclusives including Deddy Corbuzier, called “Deddy issues”, and the top 3 comedians in Indonesia called “Trio Kurnia”.

One can only wonder what will happen as they both continue to grow the audio space within Indonesia.

By the way, there is still a whole universe that we wanted to share about Indonesia. For e.g. why is horror so popular but true crime less popular, and how popular global music artists like NIKI, Rich Brian, Stephanie Poetri, can come to influence the entire category. Unfortunately we couldn’t possibly cover the whole history, but do follow us (subscribe to Podnews or read my linkedin) as we release these articles!

One more thing

If you find the article helpful at all - we’ve a favour to ask.

Speaking of edutainment, we’ve made our premium version of it, titled “Empires”.

It’s similar to Business Wars but set within Asia. As an example, we tell the monumental rise, failures, and victories that eventually birth Samsung - your smartphone and TV company that started off as a dried fish shop and now colludes with politicians (insane, right?)

Our audience are all business enthusiasts.

If you enjoyed the article we don’t ask for donations, just a quick shout out to Empires is good enough!

But as always, no pressure. Even if you don’t help us, I’m happy to connect and talk to you if you’ve any more questions.

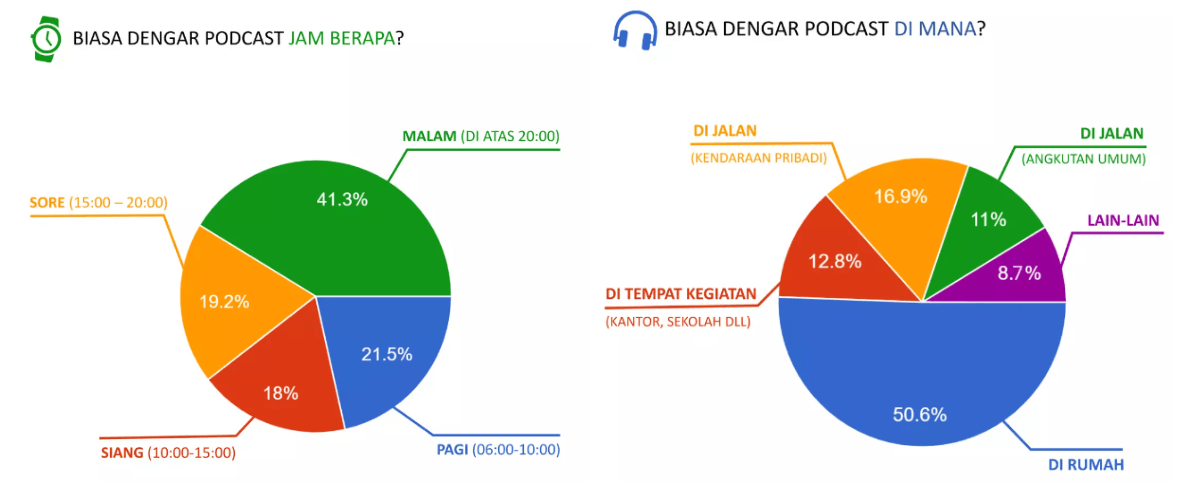

As usual, before we end things off, other interesting data worth showing to understand the landscape better:

What time & where do Indonesian’s listen to podcast: Most Indonesians listen to podcast at night to relax, and they usually listen at home after 7 pm.

Chart from Rane Hafied research, but insight based on triangulating 3 sources. - Daily Social (2018), Rane Hafied research (2019)_, Gen Z Report (2022).

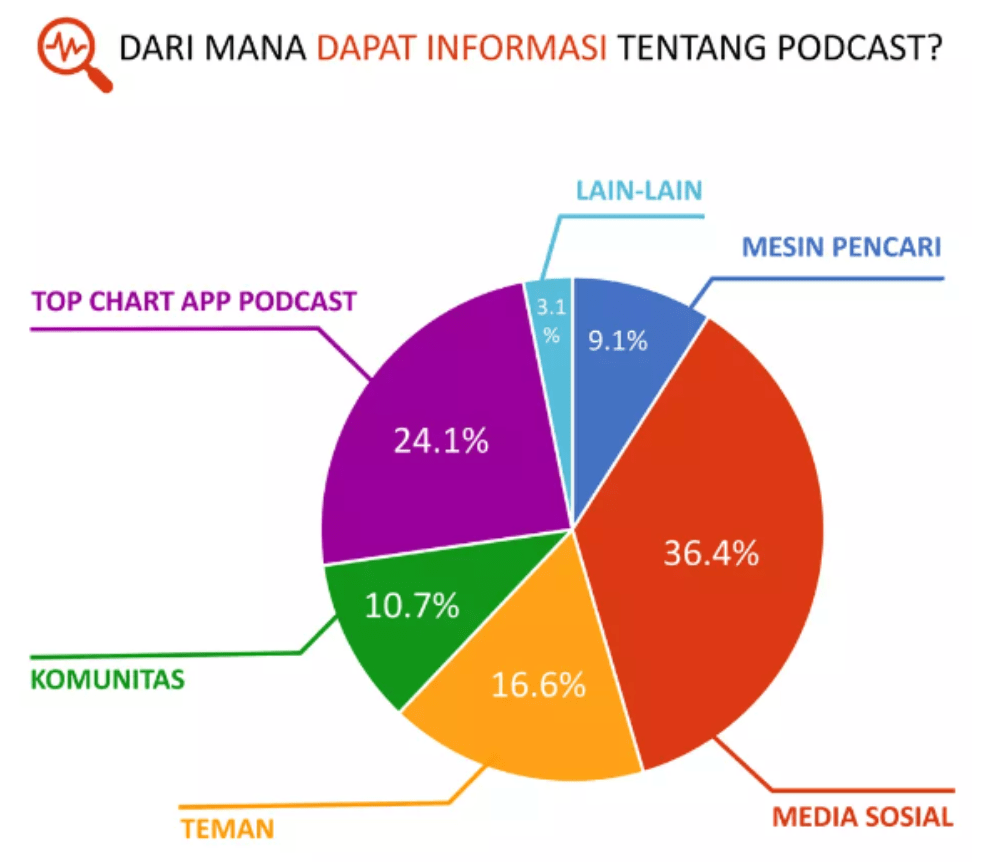

How do you discover podcasts: While social media collaterals remain the top, appearing in the top charts matters as well

Chart from Rane Hafied research, but insight based on triangulating 3 sources. - Daily Social (2018), Rane Hafied research (2019)_, Gen Z Report (2022).

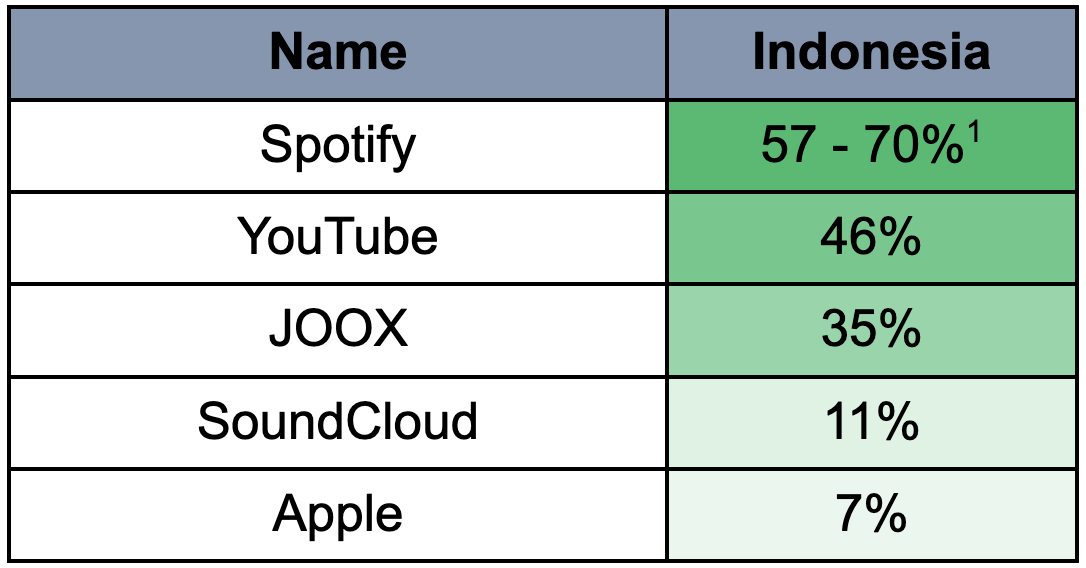

Top music listening platforms used amongst listeners of podcasts: Spotify dominates - Fun fact! The most number of anchor creators come from Indonesia.

Q3 2021, GWI.

1GWI indicates 57%, but amongst podcasters who survey their audience it seems to fall closer to 70%. It could be a misattribution of Spotify to Youtube. Additionally, Noice was not recorded in GWI, reach out for our estimates.

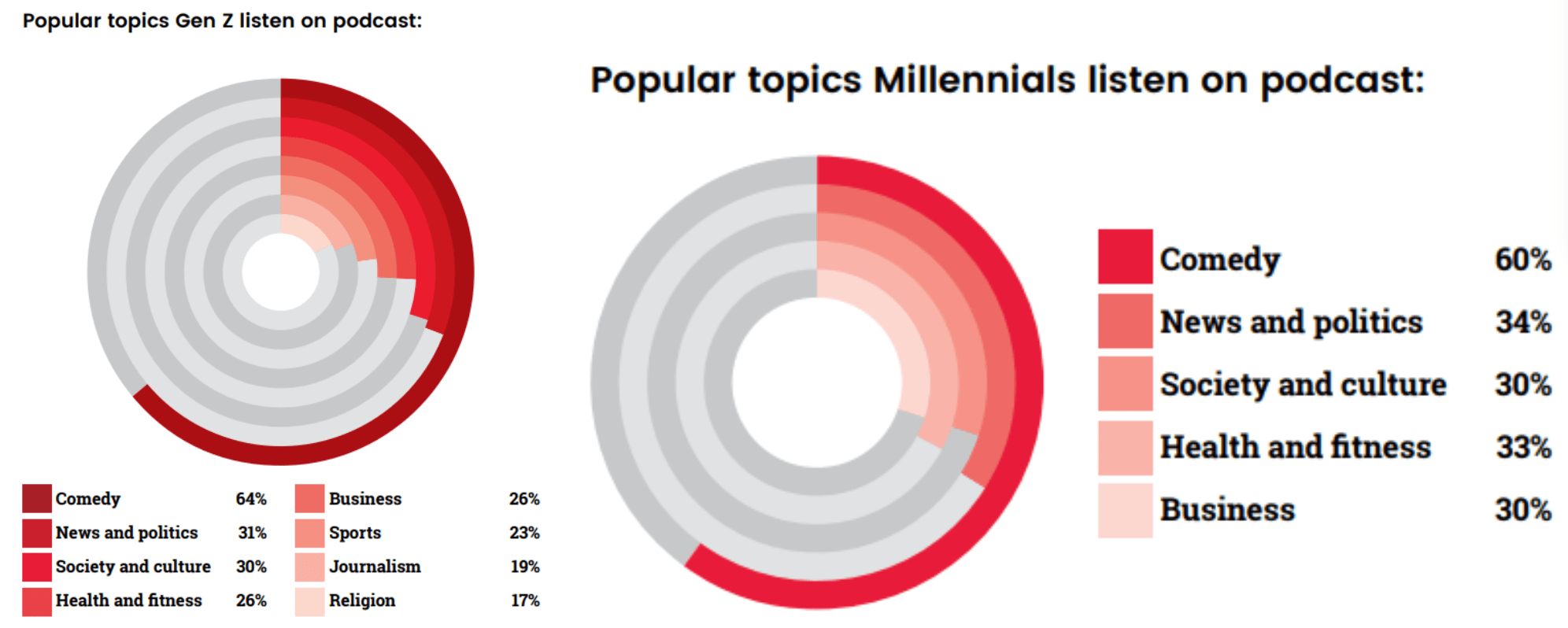

Top topics to listen on Podcast: Indonesians most favourite genre are comedy chat, news and politics, lifestyle, and health. News and Politics is fairly new - likely driven by (1) a need for worldliness, (2) newer controversial laws, (3) media news organisations readily providing it. Interestingly Spotify offers a playlist “Daily Drive” - that strings together music + podcasts for Indonesia.

Indonesia Times - Gen Z and Millennials Report.

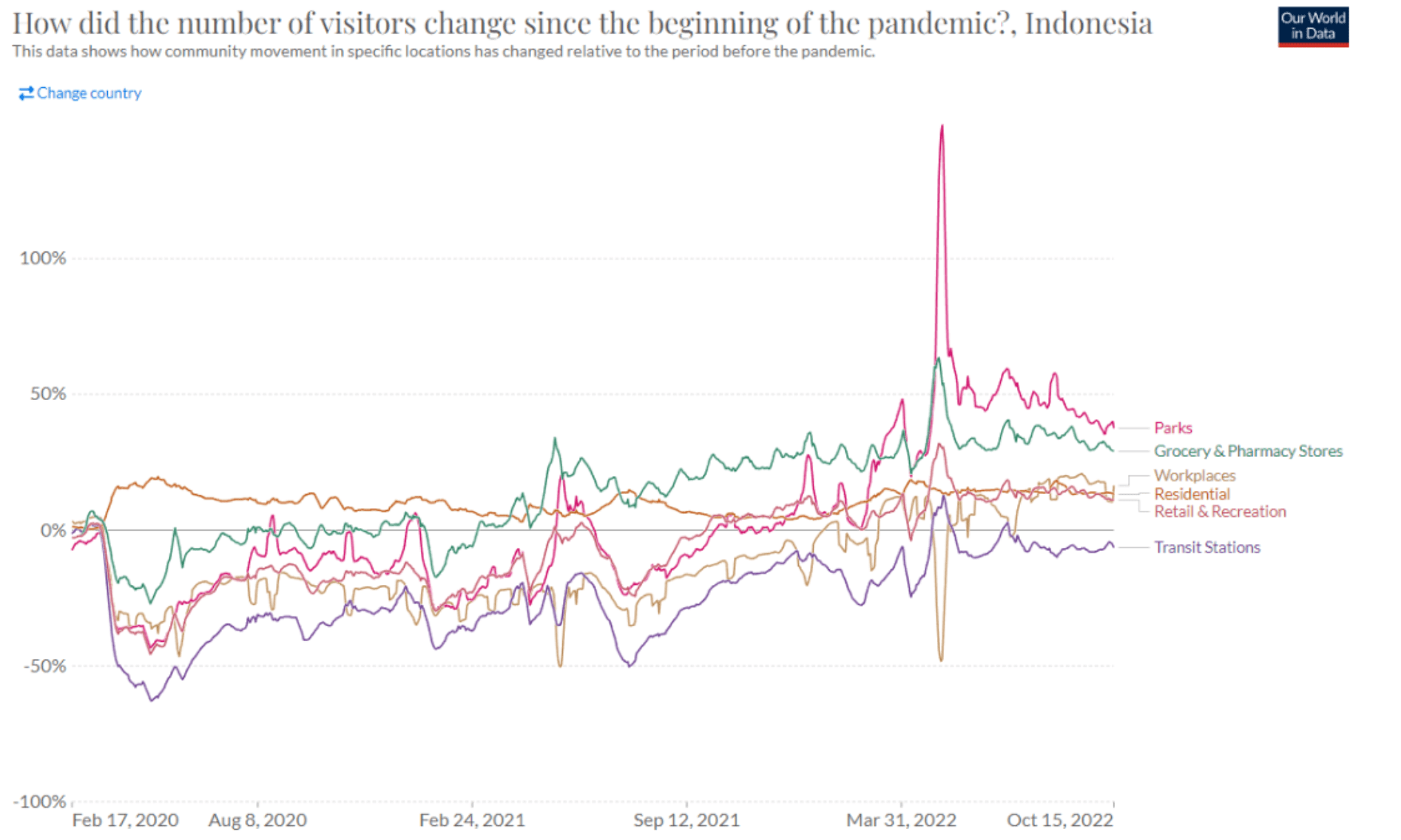

Indonesia Mobility Data - Measured as a % against the 5-week period (Jan 3–Feb 6, 2020): Surprisingly Indonesia mobility seems a little lower than pre-covid levels, since transit station movement is still a little further from baseline. However, hiking has exploded, which isn’t surprising given that Indonesia has beautiful mountains. It could also be covid deurbanisation behaviour, that lead to many to migrate back from the city.

We hope the Indonesia deep-dive gives you some confidence to explore Indonesia as a market, and to be inspired to create more truly local content. If you need any help or want to have more discussions - do drop me a LinkedIn invite, I’m always excited for conversations!

Sources:

The main bulk of the analysis is on the history of Indonesia’s podcasting, which brings together multiple data sources, and opinions. The links + GWI data is not used exclusively, rather the numbers are presented with inputs from the contributors - this enables us to triangulate a more accurate picture of the landscape’s data and history.

- Links:

https://www.telummedia.com/public/news/podcasting-in-indonesia/6zlqno4nle

https://tfr.news/articles/2022/12/21/podcast-hear-be-heard

https://kr-asia.com/indonesian-podcasters-turn-passion-into-business-tech-in-culture

https://restofworld.org/2022/meet-indonesias-joe-rogan-youtube-star/

https://www.weedutap.com/2020/05/reading-crisis-culprit-of-indonesian.html

https://techcrunch.com/2022/04/19/indonesian-audio-content-platform-noice-gets-22m-series-a/

https://kbr.id/opini_anda/09-2019/peluang_baru_itu_bernama_podcast/100697.html

Atlantic Press: How Can the Podcast Creative Industry Encourage Indonesia’s Economic Recovery during the Covid-19 Pandemic?

- Contributors

Rado Ardian, Niken Sasmaya - Co-Founders of NOICE. Rado is an ex consultant from Accenture (4 years) and an ex Googler (9 years). NOICE is the home of Indonesian audio content where listeners can enjoy a variety of exciting Podcasts, Radio, Audiobooks, and Original Series in one audio content application created by the nation’s children.

Citra Dyah Prastuti - Editor in Chief at KBR. In KBR, Citra oversees a newsroom of 25 people (radio and digital) to ensure quality journalism is delivered to their 500 radio stations under KBR’s network. Citra also oversees podcast productions under the brand KBR Prime, podcasts for curious minds’. KBR Prime collaborates with other divisions/parties to create journalism-based projects that support the issues of democracy, tolerance, environment, gender etc.

Shawn Corrigan - founder of In-Depth Creative. In-Depth Creative is an independent podcast creative company based in Jakarta with partners worldwide. We produce podcasts in both English and in Indonesian. From branded podcasts, narrative storytelling, audio documentaries to heartwarming audio dramas, we strive for independent thinking, intelligent stories, nuanced analysis, and unbound creativity.